Yes Adam Noorian (2017)

The Voice Recorder (2015)

June 6, 2015

Magdalena – (2018)

September 14, 2017Yes Adam Noorian (2017)

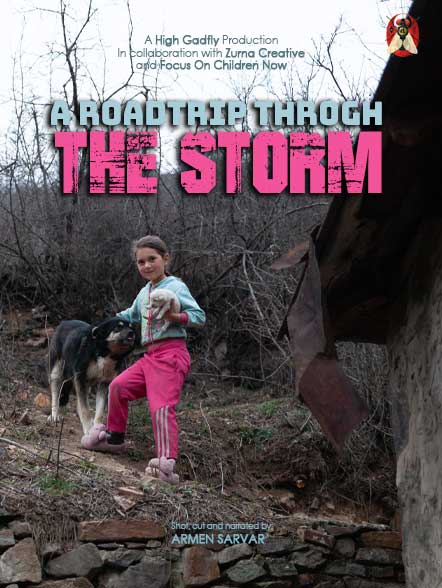

In February 2017, High Gadfly and Homentemen Ararat brought “Yes, Adam Noorian” on theater stage in Los Angeles. Inspired by Hakop Karapents’s semi-autobiographical novel “The Book of Adam”, this modern play conveyed the tale of an Armenian immigrant, who, divided between two worlds, two women, and two identities, is struggling to give meaning to his existence.

This project was the result of the collaborative work of a group of young individuals who came together and spent their time creating an innovative, diverse and quality work.

Written and directed by Armen Sarvar, and fortified by a team of professional and emerging artists, this show ran for seven nights at Atwater Village Theater and sold out entirely. This unexpected success was a proof of the fact that the Armenian diaspora did not entirely leave behind their culture and literature upon arriving to the United States.

To underline the story’s grapple with dualities, the production took the risk of opting for a bilingual performance. As a result, a meticulous translation of the text, rich with cultural references and expressions, added layers of subtext to the core story, while still being able to entertain and engage younger generations.

With the play’s successful execution of numerous daring and creative ideas, it surpassed the expectations that theater-goers may have had about an Armenian-language production of a modest budget. Bold decisions, which were initially considered absurd, paid off and despite its heavy subject matter and a hefty three-hour runtime, thanks to great ideas and performances “Yes Adam Noorian” kept its audience hooked all the way through the end, bestowing them as promised, some food for thought.

One of these stimulating ideas was a thick, translucent screen separating the audience from the inner world of Adam Noorian, further isolating our wandering protagonist from his surroundings. The screen constantly depicted Adam’s online activities and social life which in fact is a visual representation of his preferred image to the world. Once the screen descended, unmasking the true Adam Noorian, the spectators were given the chance to see a vivid image of reality and to more closely engage with the protagonist, who finally could see things as clear as the audience.

While the projection design sought to imitate the online world of the protagonist, “Yes, Adam Noorian” relied heavily on archival film and cinematic sequences. Shot and edited with attention to visual details and framing, these scenes translated Karapents’s lyrical prose into yet another visual language incorporating special effects to juxtapose past and present to create thematic transitions.

The sound design covered the storyline with matching melodies, accurate sound bites and professional foley design. In specific, a sonic motif accompanying every time that Adam remembers his wife as well as his motherland suggests a correlation between his national sentiments to his romantic ones. The sound department’s most intensive work is highlighted in a tragic flashback, where a street fight leading to a death and a funeral is conveyed entirely through a powerful audio recreation of events.

Despite these technical elements, the play never compromised its goal to echo Karapents’ social critique. Fairly unknown outside the Armenian diaspora, Karapents would consider art and literature as means of protest against the social system. Integrating his ideas with High Gadfly’s manifesto of “challenging the status quo in society”, the makers of “Yes Adam Noorian” didn’t shy away from questioning social norms such as the endless chase of the American dream, the modern obsession with social media and television, post immigration nationalistic rhetoric, denial of the importance of language in preserving ethnic culture, or the dominance of superficial entertainment. The play exhibits a strong, sarcastic take on Americanism and the pursuit of happiness. The characters’ intense obsession with TV and Facebook become biting assaults launched at those glued to their screens both on and off the stage. And while many stories in mainstream entertainment directly or indirectly urge us to chase the American dream and to embrace a consumerist society, we see Adam Noorian turning into nothing but a computer game character, running to earn credits in his pursuit of happiness. An intelligent audience would certainly spend time contemplating about this experience wondering if they too in a way are an Adam Noorian.